Royal Society Open Science: Acherontiscus - a heterodont, durophagous early tetrapod

Jenny Clack, Tim Smithson, Andrew Milner, Marcello Ruta, Keturah Smithson

Your satnav says you have reached your destination, the quaint area around the town of Loanhead, south of Edinburgh and east of Pentland Hills Regional Park. But the landscape that greets you looks unfamiliar: the town, city, and park are nowhere in sight and there are no houses, pastures or roads. You find yourself wandering amidst swamps, marshes, peat bogs, and streams, and there is lush but strange-looking vegetation all around. Sounds of splashing water from a nearby lake shatter the silence. Rasping croaks envelop you, but they are not frog calls. You have not seen or heard a single bird yet. So much for the wildlife adventures publicised in your tourist guide!

A few feet away, something is moving in the vegetation fringing the shore of a small pond. Wading cautiously through water-logged soil, you get close to a clump of clubmoss-like plants. The noise suddenly stops. Gingerly parting the plant stems, you catch a glimpse of a minuscule snake-like creature. Its tiny, elongate, and limbless body is less than six inches long. Its open mouth displays a remarkably toothy grin. It has just spotted its next meal, a small unsuspecting shrimp-like animal paddling close by. Lunging forward, it grabs its prey with its fast-snapping jaws, stabbing, slicing, and crushing it with its highly differentiated teeth. It then swims out of sight with sinuous motions of its body. Exhausted and excited, you return to your vehicle and begin to consult frantically your Scottish wildlife guide. There is no mention of the little creature.

The satnav is really acting up now. It still says you are in southern Scotland, but space and time coordinates cannot be right: you are very close to the equator … some 330 million years ago!

The above narration is fictional of course, but it does contain some facts. Firstly, the little snake-like creature is real (though nobody has ever seen it in action, unlike our imaginary tourist). Its awe-inspiring name is Acherontiscus caledoniae. It is a tetrapod vertebrate. Vertebrates are the animals with a backbone and, among them, tetrapods include today's amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, as well as the closest extinct relatives of those groups. Secondly, the region of Scotland where Acherontiscus lived was indeed near the equator and covered in wetlands in the Carboniferous Period, a time in Earth's history marked by the formation of coal deposits. Research carried out by scientists from the University Museum of Zoology in Cambridge, the Natural History Museum in London, and the Universities of Southampton and Lincoln has revealed key new data on this animal.

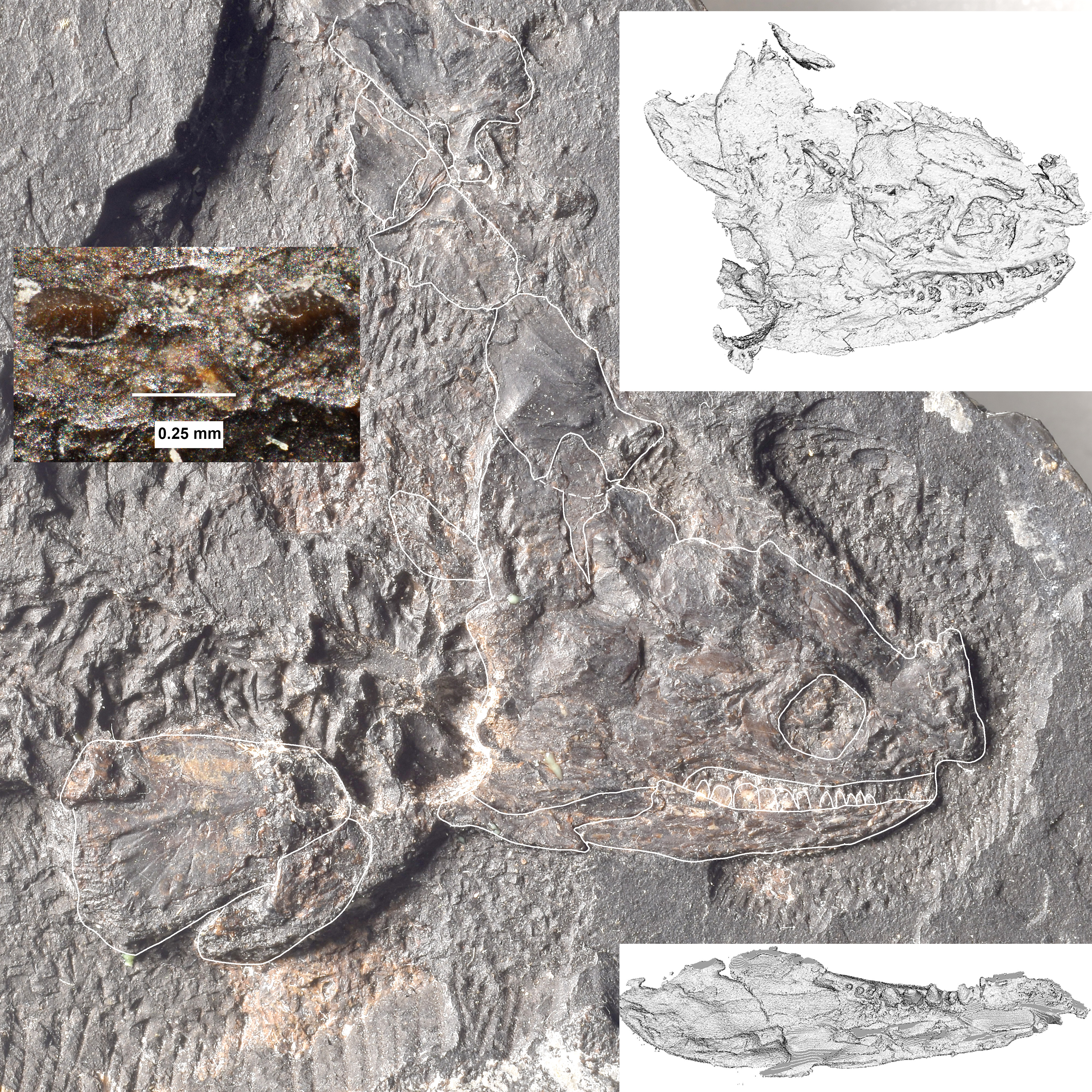

Photograph of the skull and anterior postcranium of Acherontiscus caledoniae. Bones visible on the surface are outlined in white. At lower left are elements of the shoulder girdle, and above it lie vertebrae preserved as negative spaces. At the top centre are displaced cheek bones from the left side of the skull. Also visible is the large circular orbit near the front of the short and somewhat disrupted snout. The right lower jaw is in place, and the broken crowns of the large teeth towards the back of the jaw are indicated, as are some of the smaller ones near the front. Part of the left lower jaw is protruding from the back of the skull. The skull is about 12 mm long.

The colour inset at the left shows the crowns of two of the large lower jaw teeth, showing the fluting in the enamel. The inset at bottom right shows the results of the micro-CT scan of the left lower jaw. The dentary teeth have been folded down and have penetrated the bones of the skull roof. The large teeth near the back of the jaw can be seen clearly. The inset at top right shows the micro-CT scan of the right side of the whole skull, showing bones that cannot be seen on the surface.

© Copyright Jenny Clack 2019.

Lead author Professor Jennifer Clack (University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge) said: "Acherontiscus is one of the smallest known fossil tetrapods, with a skull a little over half an inch long. Its small size and delicate nature meant that we could not use traditional methods of fossil observation under a microscope and conventional preparation using mechanical or chemical tools to free it from matrix. Using micro-CT scanning, we could visualize details of the skull roof, palate, braincase, and lower jaw for the first time, allowing us to produce a substantially revised and more complete reconstruction of this animal. We were particularly surprised to realize the remarkable diversity of tooth sizes and shapes. This animal is the earliest known tetrapod to have developed a crushing dentition, but it was also capable of simultaneously gripping and slicing through its prey. Its deep lower jaw suggests it was capable of delivering a quick powerful bite. Tiny fossil crustaceans found in the matrix surrounding the specimen may have formed a substantial part of its diet."

Co-author Dr Marcello Ruta (School of Life Sciences, University of Lincoln) commented: "The affinities of Acherontiscus have puzzled vertebrate palaeontologists since its discovery. Its unique array of skeletal characteristics is challenging. But with the benefit of new data gleaned from micro-CT scans, we decided to reassess the issue. We found a novel pattern of relationships for early tetrapods that was somewhat unexpected. Acherontiscus precedes the evolutionary separation among those early groups that would eventually lead to modern-day amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. It joins a hugely diverse array of primitive tetrapods that, independently of each other, developed a tendency for acquiring elongate trunks, small limbs, and long tails as well as, in some instances, miniaturized bodies."

Co-author Dr Andrew Milner (Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, London) explained: "Acherontiscus testifies to the sheer variety of body plans and functions in early tetrapods at a crucial time in their evolution. After tetrapods emerged from water and began to spread across the land, they experienced a remarkable rate of diversification. The newly proposed placement for Acherontiscus has immediate impact on our understanding of changes in feeding, locomotion, and sensory perception, and casts direct light on the biology and life-style of our most distant ancestors. Our re-analysis of Acherontiscus has opened new opportunities for exploring the ecology and environments of early tetrapods."

Co-author Professor John Marshall (School of Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton) added: "Periodic inundations of the wetland areas where Acherontiscus lived trapped countless organisms under layers of soil and sediments. Over millennia, increase in pressure and temperature turned plant material to coal. The rapidly buried organisms became fossilized and their remains have been unearthed from the coal seam deposits that were prospected around Loanhead at the peak of the coal mining era. Analysis of fossil spores in the matrix surrounding Acherontiscus suggests that this animal lived near or within a body of still water surrounded by herbaceous plants resembling today's clubmosses. A more distant forest of larger, tree-like relatives of present-day quillworts was also present."

Co-author Dr Timothy Smithson (University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge) said: "Other fossil tetrapods from the Loanhead area display, in various degrees, peculiar traits in their teeth, but we are still unsure about the implications of this dental diversity. Our research has highlighted persistent gaps surrounding the origin and diversification of tetrapods. This fundamental event in vertebrate history continues to benefit from new data. However, previous discoveries show considerable promise and are likely to overturn current theories."

Co-author Ms Keturah Smithson (University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge) concluded: "Through cross-disciplinary approaches and merging of expertise, the potential of fossil data in unravelling the distant past increases enormously."

The paper "Acherontiscus caledoniae: the first heterodont and durophagous tetrapod" is published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, and you can read it at: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.182087